ABSTRACT

In the context of debates on the rise of China in the West, China’s seaport investment projects in the Mediterranean region have aroused concerns in the US and the EU given that they regard China as an emerging strategic and economic challenge. The EU has strategic doubts about the security, political, and economic implications of China’s seaport investments. The EU is concerned that Beijing’s investment has geopolitical and military purposes, which might undermine internal solidarity in the EU and subvert the existing shipping structure in Europe. This study attempts to discuss how does the EU perceives China’s seaport investment and reveal whether China is a status-quo competitor or a partner for the EU in the Mediterranean. The major finding indicates that the EU had the attitude of hedging China and the US influence plays a significant role on this issue. This study put forth a clear answer on China’s seaport investments’ ‘Dilemma’.

Introduction

China has gradually become a major seaport investor in the world in the last two decades. Chinese companies have improved their participation in overseas seaport investment, and seaports have become crucial carriers for Beijing’s ‘Maritime Silk Road’ project(commonly known as the Belt and Road Initiative). Through this project, China aims at protecting and expanding its geo-economic interests.[1] The project realizes maritime interconnection and establishes an efficient and smooth market chain connecting various regions and major economies along the route. It is committed to building a comprehensive, multi-level, and composite interconnection network. Seaports remain an essential node in this interconnection.[2] China regards overseas seaports investment as a requirement for its and the stakeholders’ economic development and a must for safeguarding overseas interests.

However, China’s increasing participation in worldwide infrastructure investment projects has sparked off debates in the context of the rise of China. This complex situation is an example of the doubts and controversy aroused due to China’s overseas seaport investment. Academia and public opinion could be manipulated by the so-called geopolitical and even military purposes behind China’s overseas seaport investment. Many negative labels such as ‘neo-colonialism’, ‘military base’ and ‘debt trap’ creation have been used to describe Chinese actions. Seaport investment and construction projects along the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ have encountered serious counter attacks.[3]

Given this background, China’s growing presence and influence in the Mediterranean has drawn great attention, and seaport investment is one of the focal points. The EU has regarded the Mediterranean as within its scope of influence, and sensitive to engagement from outside powers. Although some European countries regard China’s seaport investment as an opportunity for development, many others believe that China’s expanding maritime presence poses severe economic challenges and potential geopolitical risks.[4] In the context of intensified global competition between Beijing and Washington, the EU’s perceptions towards China’s infrastructure investment in Mediterranean have become more complicated. Under the conjecture, the EU and China have seen competition and cooperation intertwined and politicized.

The context of intense global competition between Beijing and Washington as well as the rising debate on China’s overseas investment brings the questions of ‘how to understand the impact of China’s seaport investment in the Mediterranean?’, and ‘whether China in the Mediterranean is a status-quo competitor or a partner to the EU’? This article attempts to have preliminary reponse to the issue and discuss the possible approach for the EU and China to deal with the coplex challenges ahead.

Literature review and methodology

Based on different positions, people will come to different conclusions on the above questions. As previously mentioned, Chinese scholars hardly advocate that it is China’s business practices that cause strategic competition among powers. With regard to the seaport development, western powers have preconceived prejudice against China’s investment, which leads to the problem of port politicization and risks. Some studies carried out by Chinese scholars have different stances on this topic. As such, China is seeking business gains and market share by exploring its geoeconomic interests rather than geopolitical interests.[5] Others revealed the risks of China’s investment in European seaports by focusing on some seaports such as Piraeus in Greece.[6]

Although European policymakers and Western academia recognize the positive role of Beijing’s investment in the Mediterranean seaports, they are strongly concerned about its geopolitical impact.[7] European countries pay growing attention to China’s investment in Mediterranean seaports, and the fears and doubts are gradually increasing. There are different theories explaining the response given by the European countries to Beijing’s seaport investments.

Firstly, the ‘Development Opportunity Theory’ argues that China’s seaport investment might improve the seaport infrastructure of European countries and might even help some European countries’ economies that have fallen into a halt or crisis. Some people acknowledge that the EU and China share common interests in maintaining the stability of the Mediterranean, which could be a ‘sea of opportunities’ for bilateral cooperation.[8] This situation is mainly reflected in the attitudes of the Southern European countries, such as Greece and Italy.

Secondly, the ‘Market Shock Theory’, on the other hand, stresses that seaport investment from China changed or even subverted the local market pattern in Europe by bringing fierce competitive pressure and impact on the development of relevant European companies and seaports.[9] This phenomenon is more obvious in traditional seaport logistics centres in Northwestern European countries such as Germany, the Netherlands, and Denmark.

Thirdly, the ‘Strategic Threat Theory’ addresses that the current wave of China’s investment has caused some European political circles and policymakers to worry about the security and political outcomes. The major concern is that China might intensify the internal division of the EU and might undermine the EU’s geopolitical impact in the Mediterranean. Some European scholars have proposed that the EU should pay more attention to dealing with China’s rising influence.[10]

Constructivism contributes to debate by focusing on normative perspectives. Identities, perceptions, and discourses are produced and reproduced by the state elites and governments not only through documents but also via practices justifying their policies. The identities of actors are mutually constructed, foreign policy orientations also influence each other, and interests are the product of actors’ interaction within the international system. Therefore, cooperation and competition between actors could be possibly transformed into each other.

This article mainly deploys constructivist and comparative research methods to discuss the EU’s approach towards China’s seaport investment in the Mediterranean. In addition, it analyzes the documents and reports from the EU commission and Chinese authority and uses a descriptive method to summarize seaport investment projects of China in the Mediterranean. Accordingly, we focus on the above-mentioned issues and different methods in the following analytical sections. We first explain the framework of commercial seaports and military seaports dominated by the EU and the US in the Mediterranean. Then, we discuss the differences among China, the US, and the EU on the development of the seaport in the Mediterranean using a comparative analysis method. Secondly, we summarize the current situation and characteristics of China’s seaport investment in the region using the descriptive statistics and comparative methods. Thirdly, we discuss the EU’s mixed attitudes and interrogative approach towards China’s seaport investment by providing possible explanations from constructivist lenses through discourse analysis methods. Lastly, we analyse the possible approach of the EU-China seaport cooperation from the perspective of inclusive multilateralism in the future.

The EU and the US: traditional dominators in the mediterranean

The Mediterranean, as a key geopolitical and shipping hub, connects seaport and trade networks as well as multiple active economies in the world. There are many leading seaports in the Mediterranean, a dozen seaports in the Mediterranean have been listed in the world’s top 100 container seaports in recent years. The seaports on the list are mostly located in Spain, Italy, Turkey, Greece, Egypt, Malta, and Morocco.[11] The seaports in the Mediterranean have been dominated by traditional European powers for a long time. However, emerging outside powers inevitably get involved in seaport development and waterway competition in the region. The ever-increasing volume of cargo transportation and the competition of large-scale ships requires more seaport investment.[12] Nowadays, with the rapid development of international trade and seaport development demands, China has gradually become an important participant in the Mediterranean.

European countries have been dominant players in the commercial development of Mediterranean seaports. The world’s famous seaports and shipping companies, mostly located in Western European countries, have dominated the seaport development and operation in the region in the past century. The EU has special interests and huge impact in the Mediterranean region. It has always considered the Mediterranean region within its scope of influence and has established institutionalized links with the regional countries politically and economically. European companies, such as APM-Maersk, MSC, CMA CGM, Hapag-Lloyd, Eurogate, among many others, are among the top terminal operators or shipping companies in the world, and they occupy a leading and dominant position in seaport development.[13] They are also the main operators of seaports in the Mediterranean Sea and controllers of the commercial investment and development of regional seaports.

For instance, APM-Maersk, as a comprehensive global shipping logistics and terminal operator, operates 76 terminals all over the world alone or jointly, with a total container throughput exceeding 35.1 million TEUs, including seaports in the Mediterranean countries such as Spain, France, Italy, Morocco, Egypt, and Israel, among many others.[14] MSC, CMA CGM, and Eurogate are also top players engaged in the shipping and logistics business, and they occupy important position in the operation of Mediterranean seaports and sealines. MSC and its terminal investment company (TIL) own seaports and terminals in such countries as France, Spain, Turkey, and Israel. By its subsidiaries, Terminal Link, CMA CGM has invested and operated multiple terminals in France, Spain, Morocco, Malta, Greece, Egypt, and other countries. The Eurogate Group has many seaport terminals in Italy, Morocco, and Turkey in the Mediterranean region. These European companies have expanded the seaport and sealine network through intensive terminal layout and seaport investment in the last decades. With various geographical and economic advantages, they have already occupied the excellent shore-line and terminals of major seaports along the Mediterranean coast. They have also dominated the investment and development pattern of commercial seaports in the region. (See Table 1)

Sources: Terminals of TIL Group, https://www.tilgroup.com/terminals/af; APM Terminals, https://www.apmterminals.com/en/about/our-company; CMA CGM, ‘CMA CGM to operate and manage the Port of Alexandria’s future terminal’, 28 January 2021, https://www.cma-cgm.com/news/3506/cma-cgm-to-operate-and-manage-the-port-of-alexandria-s-future-terminal; Eurogate, http://www1.eurogate.de/en/.

The U.S. and NATO are the traditional shapers in seaports militarized use and pattern evolution in the Mediterranean region. The US and European powers have mostly occupied seaports with military bases building a maritime military base network and consolidating a system of alliances. Biden administration is actively rebuilding alliance system and promoting the EU to engage in the Indo-Pacific Strategy. It used to promote democratic governance and geopolitical agendas seeking exclusive scope of influence. It has the characteristics of exclusive, one-way, inequal, militarized, and security-oriented confrontational international relations. Driven by geopolitical agendas, seaports have often become important fulcrums for military deployment by the US and European powers. The ports have also become ‘bridgeheads’ to control strategic passages from the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean. The US and European powers could directly establish military bases in the seaports of countries along the route or use seaports for military stationing in ways of staying, visiting, and conducting military exercises. The US integrates military bases in Turkey, Greece, Italy, and Spain to ensure that the Mediterranean region becomes an ‘inner lake’ controlled by itself. It does not allow any non-NATO countries to control the strategic passage from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic or from the Black Sea to the Red Sea.[15] The US believes that the participation of Russia, Iran, China, and other major powers in the game has made the Eastern Mediterranean region risky to US’ interest, which poses a strategic challenge to the West and undermines the US-led security order since World War II.[16]

The US has naval bases in more than 100 seaports around the world, and its naval bases in the Mediterranean are mainly distributed in Italy, Spain, and Greece. There are four in Italy and one in Spain and one in Greece.[17] Among them, the seaports of Naples and Gaeta in Italy are the home seaports and headquarters of the Sixth Fleet, Rota in Spain, Sigoneira and Maddalena in Italy, and the Gulf of Souda of Crete Island in Greece are also its main naval bases. The Sixth Fleet is responsible for maritime security along the Mediterranean coast.[18] At the same time, U.S. Navy ships and submarines often use seaports in Israel, Cyprus, Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, and other regional countries to call, position, and supply. Among them, the port Haifa of Israel is the primary repair and logistical supply base of the Sixth Fleet. The UK has sovereign military bases in Gibraltar, Akrotiri and De Kelia in Cyprus, and Britain and France conduct regular military deployments and patrols in the Mediterranean. The European powers’ military deployment complements the US-led militarization system of Mediterranean seaports under the NATO framework. In addition, Russia has a naval base in the port Tartus in Syria on the east coast of the Mediterranean. After Russian military intervention in the Syrian war in 2015, it expanded its military presence in the Eastern Mediterranean.[19] Since 2011, the US and European powers have assembled large-scale maritime forces in the Eastern Mediterranean on many occasions using seaports in Italy, Greece, Turkey to carry out military operations and logistical supplies involved in the situation in Libya and Syria by fighting terrorism, deterring Russia and Iran, and dominating the military system of seaports in the Mediterranean. Although the primary purpose of the militarized deployment of the US and European powers is not to promote commercial interests, which of course is beneficial to their market dominance.

China: dual challenger in the Mediterranean?

China is a newcomer to seaport investment and development in the Mediterranean. In the context of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’, the Mediterranean region has increasingly attracted the attention of Chinese seaport investors. In recent years, China has expanded its cooperation with Mediterranean countries such as Greece, Egypt, Israel, Turkey, Italy, Spain, Morocco, and Algeria in seaport development. All those destinations have become a vital cooperation area and driving force for relations between China and regional countries. (see Table 2).

In the Eastern Mediterranean region, Egypt and Greece occupy a crucial role in the regional seaport and shipping structure for their unique geographic location connecting China and Europe. They have become China’s major seaport development partners. Among the critical seaports, for instance, port Piraeus in Greece is the most emphasized one with the largest investment, and it has gradually developed into a regional hub seaport. The land-sea express line can transit goods from Greece to the Central and Eastern European market, which saves time and reduces cost. Both the distance advantage of sea transportation and the convenience of rail transportation determine the success of the ‘Port Piraeus plus Land-Sea Express’ model.[20] Egypt’s seaports such as port Said and Damietta also have the potential to be regional hub seaports. In Greece, for example, COSCO Ports obtained the 35-year franchise rights of piers 2 and 3 of port Piraeus in 2008 and acquired 67% of port Piraeus in 2016. COSCO Ports’ investment directly drives the seaport to grow into the largest container port in the Mediterranean. China regards the port Piraeus in Greece as the alternative access for exports to Southeast and Central Europe and the key hub seaport for trans-Mediterranean maritime transport.[21] In 2019, the container throughout of the port Piraeus increased to more than 5.15 million TEUs, and it has developed into the largest container port in the Mediterranean and the fourth largest in Europe.[22]

Sources: Authors’ compilation of information based on Chinese official reports.

In the Western Mediterranean, China regards Italy, Spain, and Morocco as key destinations in seaport investment based on the different positioning of the countries. The seaports of northern Italy have the potential to become the new nodes of the China-Europe land-sea passage. Spain’s seaports, such as Valencia, are regional hubs, while CMA CGM, headquartered in France, has become important partners of China Merchant Port. The northern Mediterranean seaports, Barcelona in Spain, Marseille in France, and Genoa in Italy could be integrated into the European hinterland through rail and road networks.[23] Some seaports in North Africa on the southern coast of the Mediterranean are emerging in recent years, such as port Tangier in Morocco, which might change the transportation and economic landscape of the southern Mediterranean. China would focus on Italy, Spain, and Morocco in participating in the development of seaports in the region. In Italy, for example, COSCO Ports and Qingdao Port Group acquired a 40% stake in the Vado terminal and participated in the construction and operation of the Vado container terminal in 2016. In Spain, COSCO Ports acquired a 51% stake in Noatum Port Holding Company in 2017 and indirectly participated in operating terminals in port Valencia.

Obviously, China is selective in its investment in Mediterranean seaport construction and operation, depending on the trade-off of the financial, political and security risks and economic benefits, multiple factors are shaping China’s priority seaport in the region.[24] It is no doubt that China’s seaport investment and construction projects have promoted seaports development and competition in the Mediterranean. The US and the EU believe that it has not only challenged their dominance in seaport commercial development and the leadership of the region but also has raised suspicion about Beijing’s political and military agenda with commercial seaport investments. China has implemented a comprehensive seaport diplomacy plan after the port Piraeus by covering more than 20 seaports in the coastal countries of the Mediterranean region.[25]Therefore, China is regarded as a ‘dual challenger’ in the economic and military structure of the Mediterranean.

In fact, unlike the US and European powers’ engagement in seaport development, China mainly focuses on the economic attributes and interconnection value of seaports under the ‘Maritime Silk Road’. China’s seaport investment projects in the Mediterranean exhibit distinctive commercial features without involving in any military seaports. Most of China’s seaport investments are construction projects and have no equity or ownership at all and do not have rights to control and operate seaports or terminals. Several entities participate in those projects with shared benefits. Among the 11 seaport projects Chinese companies are involved in, only three seaport (terminal) projects obtain controlling stake, which is less than 30% of the total number, and only one of them has 100% equity (see Table 2). Meanwhile, there are local or international partners involved in the equity of the ports. Four of them have obtained the operation right only, directly, or indirectly involved in the operation of the terminal. In the port of Valencia, Tangier Med, Vado, Port Said and others, Chinese and European companies invest and operate adjacent terminal facilities, which are in a relationship of equal competition and even complementarity cooperation. In fact, since business activities at the ports involve multiple entities, it is difficult for Chinese companies to fully control the seaports or terminals they are involved in.

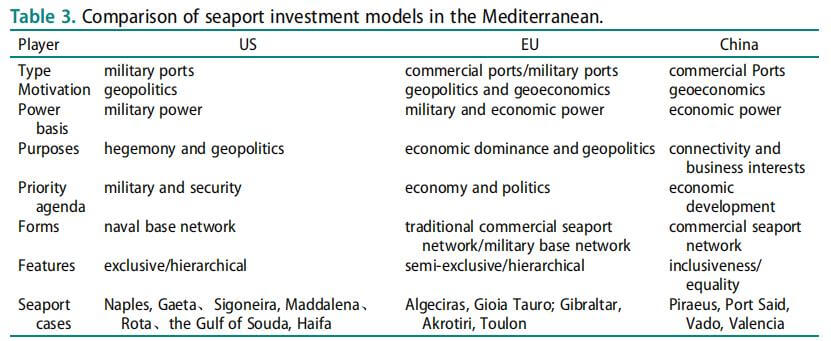

In contrast, driven by geopolitics and military power in the Mediterranean, the US maintains its hegemony and geopolitical interests based on the naval bases, and its military base network is exclusive and hierarchical. Military ports actually are part of the NATO military system, which is closed to non-allies states, and the position of each country is unequal with the US as leader in the system. European powers’ seaport development is jointly driven by geopolitics and geo-economics. They have built a dominant traditional commercial seaport network in the region by pursuing economic and security interests. With economic development as the priority agenda, China is committed to building maritime connectivity by developing partnerships; featuring openness, mutual benefit, equality; and pursuing inclusive geo-economic interests rather than exclusive geopolitical interests. In this context, an emerging ‘Commercial Seaport Network’ led by China is not only in sharp contrast with the ‘Military Base Network’ of the US but forms a competitive relationship with the traditional commercial seaports model dominated by the EU (see Table 3). Therefore, Chinese investment has promoted seaport development and commercial competition in the Mediterranean, but it has not posed a significant challenge to the US and the EU or reshape the rule and order in the region.

Sources: Authors’ compilation of information based on open reports.

The EU’s interrogative eye at China

The EU’s perception of the ‘Belt and Road’ Initiative is critical. It is full of major political doubts and it reflects the EU’s aims to shape the EU-China competition in favour of the EU.[26] In the context of intensified China-US competition and the epidemic of COVID-19, the EU is paying more attention to its relationship with China. A new consensus on China is forming within the EU, and it keeps vigilance on Beijing’s rising influence and the intentions behind it.[27] Although some European countries welcome seaport investment from China, the EU keeps vigilant and interrogative at the possible geopolitical and security impact of China’s seaport investment projects.

First, in terms of security, the EU is worried that China’s commercial seaport projects will be accompanied by military follow-up and will undermine its geographic scope of influence. The ‘China Military Base Theory’ and the so-called ‘China Pearl Chain’ argue that there are security and strategic intentions with China’s overseas seaport construction and military bases will be established to compete for geopolitical dominance after commercial seaports.[28] The US, India and some European powers have made hype and spread rumours for many years. China’s overseas seaport investment has attracted attention to a large extent from the Western media, which claim that Beijing’s investment in commercial seaports has hidden military security purposes.[29] Although many European states welcome Chinese investment in the Mediterranean, it has raised issues with regards to European competitiveness, and how to respond to Chinese naval power.[30]

Seaport investment from China has affected Europe’s idea on geopolitical security. The European powers such as Britain, Germany, France, and Italy have also been actively involved in the regional affairs.[31] The countries on the southern coast of the Mediterranean were historically colonies of European powers and have always been considered scope of influence by the EU. Geographically, the Mediterranean region is the ‘soft belly’ of Europe, and the EU is highly concerned about the security of this region and its dominance.[32] In this context, with the increasing number of seaports that Chinese companies are involved in, the EU has also begun to worry about whether Beijing’s military influence will be emerging in European countries. Although there is no public plan to turn European seaports into military bases, Chinese warships have already paid a friendly visit to the port Piraeus in Greece which has led the EU to worry about the subsequent presence of the Chinese military forces in Greece and other states.[33] As the former colonial suzerain, France and Spain have unique concerns about the Maghreb states. China’s expansion of seaport construction in the region has also aroused their vigilance, and various speculations and public rumours have also followed.

Second, politically, the EU is concerned about the influence of China’s seaport investment on EU members’ foreign policies and subsequent division within the EU on its China policy. Compared with military security concerns, the EU’s political and economic concerns are much more authentic because EU members hold different views on Chinese investment. Moreover, there is no overall EU-level policy on ports and investment screening mechanism.[34] In recent years, China has actively developed economic and trade cooperation with Central and Eastern and other sub-regions in Europe. The China-deployed desecuritised narratives of the BRI constitute an important soft power strategy of China in its engagement in Europe, while these desecuritised narratives are utilized actively by Central and Eastern countries with a political aim of negotiating their domestic interests with the EU’s institutions.[35] The EU worries that this will lead to division within the bloc, and therefore it keeps sensitive towards China’s investment.[36] Relevant reports from the EU and German leaders have addressed concerns about China’s infrastructure investment and cooperation with Central, Eastern, and Southern European countries leading to a division of the EU. The reports highlighted that this division might affect the EU’s internal solidarity and policy unity on China.[37] China’s investment in Mediterranean seaports seems to increase the difficulty for the EU to coordinate its China policy.

Seaport investment is becoming a vital power for the relationship between China and countries in the Mediterranean region. China’s investment in southern European countries, has increased their economic reliance on Beijing and caused formation of more friendly policy towards China. For instance, the COSCO’s investment in multiple seaports in Spain has brought about the rapid growth in local seaport cargo throughput, which has also brought a positive attitude towards the ‘Belt and Road’ Initiative. Local people believe that COSCO’s seaport investment would enable Chinese companies and the Spanish economy to achieve win-win cooperation. In 2017, Greece blocked the EU in issuing a statement accusing Beijing of ‘violating human rights’. Greece’s moderate attitude towards China within the EU has also been interpreted as the political influence brought by its seaport investment.[38] In recent years, the EU has repeatedly requested members to be consistent with the EU when conducting bilateral cooperation with China. In many documents and reports concerning China, it has been emphasized that a consistent policy should be formed within the EU. The EU must have a strong, clear, and consistent voice as well as a coordinated strategy towards China.[39] The EU’s document ‘EU-China: A Strategic Outlook’, issued in March 2019, defines China as a ‘competitor’ and the report specifically stress requires that ‘neither the EU nor any of its members can effectively achieve cooperation with China without complete reunification, all members have a responsibility to ensure consistency with EU laws, rules and policies in cooperation with China’.[40]

Third, economically, the EU is concerned that China’s seaport investment in the Mediterranean might overturn the European seaport and shipping structure. Traditionally, European seaport and shipping centres are mostly located in Northwestern Europe, port Hamburg in Germany, Rotterdam in the Netherlands. Antwerp in Belgium are not only the most important hubs in Europe but also the headquarters of well-known seaport and shipping companies such as APM-Maersk and Hapag-Lloyd. However, the fastest-growing seaports in Europe have been in southern Europe in recent years. Those seaports are even surpassing northern European seaports.[41] China’s seaport investment in the Mediterranean has promoted the leap-forward development of seaports in Greece, Italy, and Spain. The role of Mediterranean seaports as hub and transit centres in the European and international shipping structure is increasing.

China is increasing its economic presence in the Eastern Mediterranean, its involvement in major infrastructure projects is growing at a rapid pace and may have a significant impact on trade routes that traverse this strategically located region.[42] China’s investment has a dramatic impact on the role of European seaports and logistics hubs such as Rotterdam, Antwerp, and Hamburg. More and more Mediterranean countries tend to support China’s initiatives, and they are willing to carry out in-depth cooperation with Beijing, especially the regional countries that benefit from Chinese investment.[43] China’s seaport investment projects in southern European countries, including the China-Europe Land-Sea Express Line that China promotes, are subverting Europe’s existing trade flows and logistics patterns, which leads to an imbalance of interests within the EU and trigger other European states’ worries about falling roles of their own seaports. The development of port Piraeus along its connecting railway will significantly enhance Greece’s role in China-EU trade and communication as a hub connecting with Central and Eastern European countries, but it may divert other seaports and related trade flows.44 In this context, the traditional seaports of Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France are improving their alliances and cooperation to cope with the new competitive landscape of seaport development.

Is the EU-China comprehensive seaport cooperation possible?

Inclusive multilateralism highlights the concepts and principles of inclusiveness and common interests and focuses on transcending state-centrism and ideological differences as well as emphasizing the identity and interest orientation of the human community.[45] In terms of seaport investment, numerous entities jointly participate in the construction, ownership, operation, use; and cooperate with host country enterprises, third-party enterprises, international institutions to establish a multilateral community with shared interests, and to achieve benefit and risk sharing by serving maritime trade and the host countries’ development. This is conducive to highlighting the commercial attributes of seaport investment projects. Therefore, China should participate in overseas seaport investment in an inclusive multilateralist approach and be committed to improving international maritime services.

In the Mediterranean region, the intervention of outside powers and geopolitical games have made the region lurking with increasing risks of seaport politicization. Both the US and the EU have key strategic interests in the Mediterranean, thereby they are sensitive to the involvement of outside powers in the region. The EU is suspicious of Beijing’s infrastructure projects under the framework of the ‘Belt and Road’ Initiative.[46] Under the US pressure, the EU’s precaution against and concerns about China have gradually increased with its policies becoming conservative and deterrent. China-EU relations, therefore, are facing new challenges.[47] The EU is handling problems in bilateral economic and trade relations with a more confrontational policy. It is undergoing a new round of adjustments of its policy to China.[48] The EU fears that Beijing’s growing engagement with Mediterranean seaport development translates into its influence over regional states, and it results in an division within the EU and erosion of the EU-centred regional order. However, like in the Central and Eastern Europe, the fears are not backed by available evidence, China not only lacks the capacity to alter the strategic and policy choices of the European states, particularly at the expense of the EU, but also an intention to do so, because its relationship with the EU is much more important for China.[49] In this context, China would like to pay more attention to the impact of seaports and other infrastructure projects related to China-EU relations as well as striving to make them positive in promoting bilateral relations. While the EU put forwards and defends multilateralism as a normative power, it has always been an advocate of multilateralism in the world.[50] There are competition and cooperation between the EU and China on seaport investment in the Mediterranean, and it could be expected to promote the EU-China seaport development cooperation based on inclusive multilateralism.

First, following the principle of inclusive multilateralism, China needs to highlight the commercial and multilateral attributes of the seaport projects. China’s participation in seaport development in the Mediterranean should follow the principles of marketization and commercialization through combining its own experience, capabilities, and local advantages to achieve mutual benefit through the inclusive design of seaport construction, operation, and utilization.

EU’s new FDI regulations law came into effect in April 2019.[51] Infrastructure investment projects involved by Chinese state-owned enterprises are the focus suspects of the EU’s investigation. The primary driving force of China’s seaport investment lies in the globalization needs of companies and their global commercial layout. Chinese companies has to involve in global competition, otherwise they cannot survive in new era. China pays attention to highlighting commercial attributes in seaport investment in the Mediterranean, actively supports Chinese-funded enterprises to follow market principles in independent decision-making and participate in international commercial competition. Furthermore, Chinese companies should actively adopt localized operations, collaboration, and cooperation to avoid risks. They should also share equity with multiple investors such as host country and international financial institutions in order to avoid zero-sum games and reduce the risk of seaport politicization. Chinese companies need to strengthen multi-level and in-depth cooperation with well-known European companies such as Maersk, CMA CGM, MSC, Eurogate, Hapag-Lloyd, among many others. For example, China Merchants Port’s participation in the operation of more than ten seaports and terminals by acquiring the shares of Terminal Link in 2013, most of which are in the Mediterranean Sea.[52]

Second, the EU and China need to expand the strategic alignment, integration of interests, and win-win cooperation. Against the controversy on intentions and perceived political interventions, Beijing must fully consider the geopolitical and geostrategic concerns of other powers.[53] Although there are competitions between China and the EU on seaport development, it is a market-oriented behaviour under the premise of following global business rules instead of political adversary. The two sides have potential in seaport development cooperation.

In response to EU’s strategic doubts and concerns, China needs to adopt a more open approach to improve mutually beneficial cooperation with the host country and align with EU’s interests through joint development, equity transfer, and interest sharing, thereby realizing the integration of interests and reducing the EU’s strategic doubts. Both sides should further strengthen the connection ‘Eurasian Interconnection Strategy’ and ‘Global Gateway’, proposed by the EU, with the ‘Belt and Road’ Initiative into which the seaport development cooperation could be included. In recent years, seaports in Greece, Italy, and Spain have been on the priority agenda of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ due to Chinese investment. They have received support from the container fleet of Chinese companies such as COSCO Shipping and have ushered in new development opportunities. They therefore have seen the benefits of Chinese seaport investment hoping that more Chinese investment will drive the expansion of local seaport logistics and trade. Seaport investment projects in the Maghreb region should focus on joint development with France and Spain, which are relatively more significant to the region to reduce potential geopolitical risks. It is not only necessary to reduce vicious competition and enhance interest integration through third-party cooperation for China and the EU, but also to integrate seaport cooperation into the agenda of bilateral strategic dialogue.

Meanwhile, the EU and China could enhance regional governance cooperation in the Middle East and North Africa through seaport infrastructure projects. The social and security situation in the Middle East and North Africa on the eastern and southern coasts of the Mediterranean is complex with multiple challenges. The EU and China could cooperate to provide international public goods and promote the development of countries in the region by seaport investment. This will not only help reduce the political and security sensitivity of China’s seaport investment, but also promote a multilateral governance process in the Middle East and North Africa.

Third, the EU and China have to keep precautious to the strategic interference of the US. Against the background of China-US global competition, the US requires European allies to take a much more strict policy against Beijing and conduct strategic coordination on the issue of China’s infrastructure investment.[54] In the context of the increasing pressure from the US, seaports investment along the ‘Maritime Silk Road’, including the Mediterranean region, is not only an important area that easily triggers strategic competition between Beijing and Washington but also gradually affects China’s relationship with the EU.

As China’s infrastructure investment in Europe has continued to increase, the US has persuaded the EU to contain Beijing’s seaport investment jointly,[55] and it has put increased pressure on countries in the region to interfere and obstruct China’s seaport investment projects.[56] As these countries develop close economic ties with China, they will be inclined to avoid having to choose sides between Washington and Beijing when these two have differing views on regional issues. This development would limit the strategic options for the US in the region.57 As a result, Washington has strengthened its defences against Beijing and restrained its allies. For instance, the US has made it clear that the Israeli government should not be handed over to SIPG to operate the port Haifa on the grounds of security issues.[58] Similarly, the US has put pressure on Greece, Italy, Israel, and other regional countries with obvious intentions to target Chinese investment and contain China’s influence. The EU’s perception and policy on China’s seaport investment are significantly shaped by Washington.

Conclusion

This article explores the dynamics and consequences of China’s seaport investment in the Mediterranean and the EU’s interrogative approach, which have become an increasingly critical issue for both sides. The article further argues that China’s seaport investment has no political agenda. To this end, it adopts constructivist and comparative research methods to analyse the research question. The region is a crucial link connecting Asia with Europe along the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ from a holistic perspective. China’s involvement has dramatically changed the structure of seaport development in the region and exerted an impact on China’s relations with regional states. This development put China under the spotlight. Due to the interconnection of seaports, regional countries’ policies towards the ‘Belt and Road’ Initiative, and Mediterranean countries’ active cooperation with China, trade and investment have grown significantly. In this regard, seaport competition in the Mediterranean has become an important issue in EU-China relations, which has also been an emerging opportunity for both sides.

It is important to mention that the US administration builds an alliance system with the EU to engage in the Indo-Pacific Strategy. The US and the EU have improved coordination on the ‘China issue’. Although some European countries welcome Beijing’s investment in Mediterranean seaports and regard it as a development opportunity, the EU’s strategic doubts are rising. It is likely to follow the US in hedging or containing China’s seaport investment projects. In response to the EU’s concerns and possible hedging policy with the US, China needs to strengthen dialogue and cooperation with the EU by pursuing mutual benefit and win-win cooperation. Such a relation strives to keep the EU and China partners rather than rivals. China needs to do its best to improve maritime cooperation and integration of interest with the EU in seaport investment in the Mediterranean and pay attention to the complex impact of infrastructure projects on the China-US-EU triangle relationship.

Notes

- J. Chen, Y. Fei, Paul Tau-woo Lee & X. Tao, ‘Overseas port investment policy for China’s central and local governments in the belt and road initiative’, Journal of Contemporary China, 28(116), 2019, p. 196.

- X. Zhao, X. Liang, Q. Zhou, and Y. Zhao, ‘EvoluTion of spatial pattern of port system along maritime silk road’, Journal of Shanghai Maritime University, 38(4), 2017, p. 48.

- Z. Zou and D. Sun, ‘The politicization of ports: political risks of China’s participation in port construction along the 21st century maritime silk road’, Pacific Journal, 28(10), 2020, pp.80–94.

- Oziewicz, Ewa, and Joanna Bednarz, ‘Challenges and opportunities of the maritime silk road initiative for EU Countries’. Zeszyty Naukowe/Akademia Morska W Szczecinie, Zeszyty Naukowe/Akademia Morska w Szczecinie, 59 (131), 2019, pp. 110–19.

- Z. Zou & D. Sun, ‘China’s seaport diplomacy in the eastern Mediterranean: Features, Dynamics and Prospects’, China: An International Journal, 19(4), 2021, p. 104.

- ‘Report on China’s overseas port projects under the belt and road’, Grandview institute, April 2019, http://www.grandviewcn.com/Uploads/file/20200304/1583310568527774.pdf(accessed 12 April 2021); X. SANG, ‘Problems and potential risks of China’s port investment in Europe: the Port of Piraeus as an Example’, International Forum , 21(3), 2019; B. Wang, P. Karpathiotaki, and C. Dai, ‘The central role of the mediterranean sea in the BRI and importance of piraeus Port’, Journal of WTO and China, 8(4), 2018.

- F. P. van der Putten & M. Meijnders, ‘China, Europe and the maritime silk road’, Clingendael Report, 2015, https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/China_Maritime_Silk_Road.pdf; F. P. van der Putten, ‘The geopolitical relevance of piraeus and China’s new silk road for Southeast Europe and Turkey’, Clingendael Report, 2016, https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/Report_the%20geopolitical_relevance_of_Piraeus_and_China’s_New_Silk_Road.pdf (accessed 21 May 2021); F. P. van der Putten, ‘Infrastructure and Geopolitics: China’s emerging presence in the eastern Mediterranean’,Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies, 18(4), 2016; F. Godement, D. Pavlicevic, A. Kratz, A. Vasselier, M. Rudolf, and J. Doyon, ‘China and the Mediterranean: Open for Business?’,European Council on Foreign Relations, 21 June 2017, https://ecfr.eu/wp-content/uploads/China_Analysis_June_2017.pdf (accessed 15 October 2021).

- R. Prodi, ‘A Sea of opportunities: The EU and China in the Mediterranean’, Mediterranean Quarterly, 26(1), 2015.

- A. Ekman, ‘China in the Mediterranean: an emerging presence’, Notes de l’Ifri, Ifri, February 2018.

- K. Johnson, ‘Why is China buying Up Europe’s ports’, Foreign Policy, 2 February 2018, https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/02/02/why-is-china-buying-up-europes-ports; Vali Pandya & Simone Tagliapietra, ‘China’s strategic investments in Europe: The case of maritime ports’, 27 June 2018, https://www.bruegel.org/2018/06/chinas-strategic-investments-in-europe-the-case-of-maritime-ports/; Joanna Kakissis, ‘Chinese firms now hold stakes in over a dozen European ports’, NPR, 9 October 2018, https://www.npr.org/2018/10/09/642587456/chinese-firms-now-hold-stakes-in-over-a-dozen-european-ports; ‘Concerns grow over china’s influence on European ports’, NPR, 10 October 2018, https://www.npr.org/2018/10/10/656079724/concerns-grow-over-chinas-influence-over-european-ports; Helen Raleigh, ‘The European Union finally recognizes China as a dangerous rival, without taking action’, The Federalist, 25 March 2019, https://thefederalist.com/2019/03/25/european-union-finally-recognizes-china-dangerous-rival-without-taking-action/(accessed 25 April 2021).

- Lloyd’s List, ‘One hundred container ports 2019’, 29 July 2019, https://lloydslist.maritimeintelligence.informa.com/one-hundred-container-ports-2019 (accessed 22 July 2021).

- G. Lauriat, ‘Mediterranean sea-ports in the middle’, AJOT, 28 October 2019, https://ajot.com/premium/ajot-mediterranean-sea-ports-in-the-middle (accessed 8 September 2021).

- Lloyd’s List, ‘Top 10 box port operators 2019’, 1 December 2019, https://lloydslist.maritimeintelligence.informa.com/LL1130163/Top-10-box-port-operators-2019; ‘Top 30 international shipping companies’, MoverFocus, 27 September 2019, https://moverfocus.com/shipping-companies/; ‘The World’s leading container ship operators based on number of owned and chartered ships’, Statista, 4 May 2020, https://www.statista.com/statistics/197643/total-number-of-ships-of-worldwide-leading-container-ship-operators-in-2011/; UNCTAD, ‘Review of maritime transport 2019’, 30 October 2019, https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/rmt2019_en.pdf (accessed 22 June 2021).

- APM Terminals, https://www.apmterminals.com/en/about/our-company (accessed 21 November 2021).

- D. Sun, The U.S. Military Bases in the Greater Middle East: Deployment and Trend of Readjustment, Beijing: Current Affairs Press, 2018, p. 124.

- J. B. Alterman, H. A. Conley, H. Malka, and D. Ruy, ‘Restoring the eastern mediterranean as a U.S. strategic anchor’, CSIS, 22 May 2018, https://www.csis.org/analysis/restoring-eastern-mediterranean-us-strategic-anchor (accessed 12 October 2021).

- See ‘Navy Bases’, Military bases, https://militarybases.com/navy/(accessed10 November 2021).

- D. Sun, ‘The Four Dimensions of the US Military Base Deployment Abroad: A Case of the Greater Middle East’, International Review, 146(2), 2017, p. 88.

- E. Rumer and R. Sokolsky, ‘Russia in the Mediterranean: Here to stay’, Carnegie endowment for international peace, 27 May 2021, https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/05/27/russia-in-mediterranean-here-to-stay-pub-84605 (accessed 20 November 2021).

- X. Sang, op. cit. p. 27.

- F. P. van der Putten, ‘Infrastructure and geopolitics: China’s emerging presence in the eastern Mediterranean’, op. cit., p. 341.

- See Annual report released by COSCO Ports, https://doc.irasia.com/listco/hk/coscoship/annual/2019/car2019.pdf (accessed 21 June 2021).

- ‘Mediterranean ports’ competences and competitions’, docks the future, 11 November 2020, https://www.docksthefuture.eu/mediterranean-ports-competences-and-competitions/(accessed 26 July 2021).

- Z. Zou & D. Sun, op. cit., p. 108.

- G. F. Rhode, ‘China’s emergence as a power in the Mediterranean: Port diplomacy and active engagement’, Diplomacy and Statecraft, 32(2), 2021, p. 394.

- Z. Wang, ‘EU institutions’ perceptions towards BRI and China’s coping measures: Multilevel alignment based on EU perceptions and competences’, Pacific Journal, 27(4), 2019, p. 67.

- J. Oertel, ‘The new China consensus: How Europe Is growing wary of Beijing’, European Council on Foreign Relations, September 2020, https://www.ecfr.eu/publications/summary/the_new_china_consensus_how_europe_is_growing_wary_of_beijing(accessed 22 October 2021).

- Michael J. Green, ’China’s maritime silk road: StrateGic and economic implications for the indo- pacific region’, CSIS, 12 April 2018, www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-maritime-silk-road; James Kynge, “How China rules the waves’, Financial Times, 12 January 2017, https://ig.ft.com/sites/china-ports/ (accessed 20 June 2021); Jayanna Krupakar, ‘China’s naval base(s) in the Indian Ocean—Signs of a Maritime Grand Strategy?’, Strategic Analysis, 41(3), 2017, p. 207.

- J. Kynge, C. Campbell, A. Kazmin and F. Bokhari, ‘How China rules the waves’, Finacial Times, 12 January 2017, https://ig.ft.com/sites/china-ports/ (accessed 25 April 2021).

- M. Duchâtel, ‘Blue China in the Mediterranean, beyond port management’, Italian Institute for International Political Studies, 4 February 2019, https://www.ispionline.it/en/pubblicazione/blue-china-mediterranean-beyond-port-management-22161 (accessed 23 Septebmer 2021).

- Z. Tziarras, ed., ‘The new geopolitics of the eastern Mediterranean: Trilateral partnerships and regional security’, Re-imaging the eastern Mediterranean series: PCC Report 3, Friedrich Eberto Stiftung, 2019, pp. 6–7.

- L. Song, ‘The Eruopean-mediterranean partnership development: The Perspective of EU’s external governance’, Tongji University Journal Social Science Section, 22(6), 2011, p. 67.

- J. Kakissis, op. cit.

- R. H. Linden, ‘The new sea people: China in the Mediterranean’, Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI), July 2018, p. 14.

- M. Jakimów, ‘Desecuritisation as a soft power strategy: The belt and road initiative, European fragmentation and China’s normative influence in Central-Eastern Europe’, Asia Europe Journal, 17(4), 2019, pp. 369–385.

- J. Long ‘Retrospect and Prospect of “+Multispeed Europe” and analysis of the impact on China-Europe relationship’, Peace and Development, 158(4), 2017, p. 94–95.

- H. Wang, ‘The EU’s attitude to China-Central and Eastern European states cooperation, dynamics and policy’, Development Studies, 7, 2018, pp. 58–59.

- V. Pandya and S. Tagliapietra, ‘China’s strategic investments in Europe: The case of maritime ports’, Bruegel, 27 June 2018, https://www.bruegel.org/2018/06/chinas-strategic-investments-in-europe-the-case-of-maritime-ports/; Joanna Kakissis, op. cit.

- European Commission, ‘Joint communication to the European parliament and the council: Elements for a New EU strategy on China’, 22 June 2016, https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/joint_communication_to_the_european_parliament_and_the_council_-_elements_for_a_new_eu_strategy_on_china.pdf (accessed 22 June 2021).

- European Commission, ‘EU-China: A strategic outlook’, 12 March 2019, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/news/eu-china-strategic-outlook-2019-mar-12_en(accessed 22 June 2021).

- T. Notteboom, ‘Top EU container port regions (2007–2016): The rise of South Europe’, Port Economics, 31 July 2017, http://www.porteconomics.eu/?p=5064; ‘Med Ports Surpass Northern Europe in Container Transport’, ANSAmed, 6 June2018, http://www.ansamed.info/ansamed/en/news/sections/transport/2018/06/06/med-ports-surpassnorthern-europe-in-container-transport_90572573-4e2c-44c9-bf92-98e889f3d776.html(accessed 24 September 2021).

- F. P. van der Putten, op. cit., p. 337.

- A. Ekman, ‘China in the Mediterranean: An Emerging Presence’, Notes de l’Ifri, Ifri, February 2018.

- Z. Wang, ‘EU Institutions’ Perceptions towards BRI and China’s Coping Measures: Multilevel Alignment Based on EU Perceptions and Competences’, Pacific Journal, 27(4), 2019, p. 68.

- Y. Qin, ‘The Change of World Order: From hegemony to Inclusive multilateralism’, Asia-Pacific Security and Maritime Affairs, 2, 2021, p. 13.

- R. Roccu & B. Voltolini: ‘Framing and reframing the EU’s engagement with the Mediterranean: Examining the Security-stability Nexus before and after the Arab uprisings’, Mediterranean Politics, 23(1), 2018, p. 1.

- Z. Hu, ‘The Diverse Dilemmas of the European Union and China’s Europe strateg’, People Forum: Frontiers, 167(6), 2019, p. 42.

- K. Zhao and G. Li, ‘Impact of EU industrial structure changes on China-EU economic and trade relations’, International Trade, 4, 2020, p. 72.

- D. Pavlićević, ‘A Power Shift Underway in Europe? China’s relationship with central and eastern Europe under the belt and road initiative’, In X. Li, (ed), Mapping China’s ‘One Belt One Road’ Initiative, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019, p. 270.

- F. Song, ‘EU’s hard choice between China and the United States: An analysis based on the perspective of Cakeism’, Global Review, 13(3), 2021, p. 92.

- European Union, ‘Regulation (EU) 2019/452 of the European parliament and of the council of 19 March 2019 establishing a framework for the screening of foreign direct investments into the union’, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/452/oj (accessed 28 August 2021).

- Among them, the ports of Marseille-Fos, Tangier, and Marsaxlokk are located on the Mediterranean.

- P. Liu & P. Pandit, ‘Building ports with China’s assistance: Perspectives from Littoral Countries’, Maritime Affairs: Journal of the National Maritime Foundation of India, 14(1), 2018, 99–107.

- F. Song, op. cit., p. 94; H. Zhao, ‘Brussels’ strategic choices amid China-U.S. Competition and EU-U.S. Policy coordination on China’, Global Review, 13(5), 2021, p. 4.

- ‘Europe, COVID-19, and U.S. Relations’, Congressional research service, 14 January 2022, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11635 (accessed 7 March 2022).

- Alexy Zender, ‘US and China Struggle for hegemony on cyprus and the eastern Mediterranean’, Beyond the Horizon, 22 January 2019, https://behorizon.org/us-and-china-struggle-for-hegemony-on-cyprus-and-the-eastern-mediterranean/(accessed 8 March 2022).

- F. P.van der Putten, op. cit., p. 345.

- M. Wilner, ‘U.S. Navy may stop docking in haifa after Chinese take over Pot’, The Jerusalem Post, 15 December 2018; R. Kampeas, ‘Breaking China: A Rupture Looms between Israel and the United States’, The Jerusalem Post, 3 June 2020.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Funding

The work was supported by the Chinese National Funding of Social Sciences [19FGJB017].

Notes on contributors

Zhiqiang Zou is a Research Fellow at Center for Middle Eastern Studies, Institute of International Studies of Fudan University, Shanghai, China. His recent articles have appeared in China: An International Journal and Asian Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies. (Corresponding author)

Ahmet Faruk Isik is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Comparative Politics and Area Studies at Shanghai International Studies University. He is a researcher in the Italy Torino World Affairs Institute and research assistant of the Shanghai Academy of Global Governance and Area Studies (SAGGAS).

![Olympic village [Photo provided to Beijing Daily]](http://sisu.cdn.1fenda.com/sites/default/files/2022-10/Olympic%20village.jpg)